Introduction

Confounders are behind some so-called "spurious correlations", or those correlations that we've all been taught from statistics education infancy "do not imply causation". Certainly some spurious correlations are truly spurious, as in, purely coincidental. Google Correlate was a fun place to find some of those. But in science, a bigger problem is the not-really-spurious "spurious correlations" which appear in data due to confounders.

Here's an exmaple due to William Burns: The number of fire trucks at a fire correlates with the amount of damage at that same fire. The correlation of course doesn't imply that the fire engines are the cause for the damage (nor that the damage produces fire trucks). There is a confounder at play, the severity of the fire, which causes both the number of fire engines, and the damage. As a personal note, I don't think it's a spurious correlation (on linguistic merit), but this is the kind of correlation scientists call spurious - ones that aren't due to direct causation.

So these confounders make it difficult to assess the relationship between two variables; it might make you think one exists where one does not. To get around these, statisticians "control for" confounding variables. In the example above, if we split the fires into groups of similarly severe fires, within each group, no positive correlation between the number of fire trucks and damage would appear - in fact, quite possibly the opposite would become apparent, that sending more fire engines leads to less damage (anticorrelation). This might even be a causal link.

So when trying to figure out if a correlation is spurious or meaningful (perhaps even causal), the problem we're facing is that of identifying confounders, measuring them, and controlling for them.

Randomized Controlled Trials

In many real-world cases, even the first task, identifying confounders, is impossible. We simply don't know all the variables that might affect both of our measures. We don't know all the causes for fire damage and which of those might also affect the number of fire engines present; we certainly don't know all the factors which affect a person's predisposition to develop a disease, or respond to a certain drug! The medical research community is usually interested in finding causal links between treatments and responses (e.g. does a drug work?), and has settled on a solution for the spurious correlations problem: the Randomized Controlled Trial. The problem of course is deciding whether a certain therapy is effective against a certain disease, i.e. is taking the drug correlated with getting better, and if so, is this a spurious correlation? Because there may be confounders causing both the disease and the response to the therapy. For instance, what if there's some selection bias in who takes the drug, that is, what if men are more likely to take the drug than women, and it also happens to work better for men? It could be worse - what if doctors only perscribe the drug to patients who are more likely to survive anyway?

The solution, due to one of the fathers of modern statistics, Ronald Fisher, is simple: if you don't know all the possible factors which affect the outcome (response to therapy), and thus you cannot control for them when administering the treatment, you should randomize your treatment! That way, *on average*, you will control for all possible confounders. And Fisher went on to develop the statistical tools to estimate just how much uncertainty you have in each experiment, since they are only guaranteed to work perfectly on average.

Using causal models to identify confounders

Randomized trials are great when all of the confounders can't be identified and the experimenter can assign the treatment. However, often we deal with so-called observational data, when an experimenter can observe some data points, but may not assign treatments, e.g. for ethical or practical reasons. In this scenario, a very common thing researchers do, is treat anything you can measure as a potential confounder, and control for everything. An only slightly more clever variant of this is to measure the correlation between all the variables, and *control for all the correlated variables*. But I recently learned of a more elegant way of de-confounding data, which also works on observational data. The crux of the problem is, this requires an explicit causal model between all relevant variables. The flip-side is, it's always a good idea to make your causal assumptions about the system you're studying explicit anyway!

This method is due to Judea Pearl1 in 1995, and I'll illustrate it with a couple of examples from Clarice Weinberg, who first published them in 19932, and later revisited them using Pearl's methodology as well3.

The explicit causal model

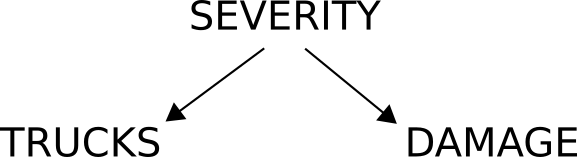

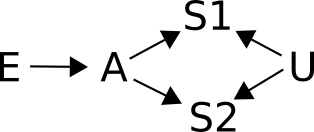

First off, sketch a graph which makes explicit your assumptions about what causes what. This is the hard part. For the fire truck example above, the causal diagram might look like this:

This is what a typical confounder looks like - it causally precedes both variables which it confounds. Looking at this causal diagram, we can see that DAMAGE and TRUCKS are confounded by the severity of the fire. If we control for the severity of the fire then, the number of trucks and the amount of damage should be independent, i.e. not correlated.

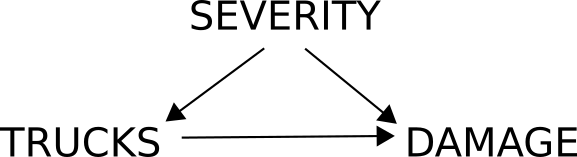

If on the other hand we suspect that the presence of more trucks might actually affect the damage, we could draw the following diagram:

What this diagram shows you is that, if you'd like to quantify the effect trucks have on damage, you need to control for severity, because it is a confounder. But in this analysis, we don't expect trucks and damage to be independent, because there is an arrow between them; we do however see that they are confounded by severity, and so severity needs to be controlled for before we compute any correlations. Otherwise, we'll never know if the correlation we find is only due to severity, or due to an actual effect of trucks on damage (which might even be a reversal in the direction of the correlation, if more trucks lead to a quicker response and thus to less damage!).

Spotting (in)dependence in the causal model

There are simple tricks that can help you decide, for each triplet in a causal diagram, if there is a confounder at play, or how to know which variables should be independent.

Chains

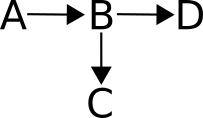

The simplest triplet looks like this:

A -> B -> CIn this case, we expect A to have an effect on C, but only through B. B is called a "mediator". There is no confounding at play here; C is dependent on A via B. If we control for B, we end up severing the causal chain between A and C, which makes A and C independent. If we wish to examine the strength of the relationship between A and C, controlling for B would be disastrous, as it would render them independent.

Forks

A <- B -> CThis is the classic confounding variable case. B confounds A and C. If we'd like to examine the relationship between A and C, we would first need to control for B, otherwise we're really measuring the effects of B on A and C. As this diagram stands, A and C are not independent. Controlling for B makes them so.

Colliders

Colliders are the opposite of a fork:

A -> B <- CHere, both A and C affect B. As the diagram stands, A and C are independent. If we wanted to quantify the relationship between A and C, should we then control for B? The answer is a resounding no. In fact, controlling for B here will make A and C dependent! This is called the "explain away" effect, or the "why are the pretty ones so dumb?" effect. Imagine that A stands for a person's physical attractiveness, and C for their intelligence. B is the likelihood you'll be talking to them. This is because in this model, you are likely to strike a conversation with a person if they are pretty, and you're also likely to strike up a conversation with a person if they're smart; either on its own will compel you to talk to them. A-priori, let's assume intelligence and looks are independent (no arrow between A and C, and no confounder either). But what happens when we control for B? That is, when we only look at your conversation partners? Well, then what happens is that A and C become anti-correlated! That is, if a person you're talking to is good looking, they are more likely to be dumb. Because their good looks "explain away" how come you're talking to them. Yeah, it's a thinker... But think about the other group too - the people you're not talking too. According to this model, they are more likely to be both dumb AND unattractive (spurious correlation) than the general population (no correlation). Controlling for a collider makes its (independent) causes conditionally dependent.

Proxies - partial deconfounding

Consider the following:

In this example, A causes D via B. And B also causes C. This scenario is common enough if the mediator (B) is not directly measurable, but some side-effect of B, say, C, is measurable. Then C is called a "proxy" for B. Should C be controlled for when assessing relationships between A and D? The answer is that controlling for C, being a proxy for B, is in effect a "partial" control for B. And we already know we don't want to control for the mediator B.

The backdoor criterion

Now to the best part - how can we use all that to know when we have confounding? and which variables should we control for when assessing relationships between treatment and response? The answer is the backdoor criterion, from Pearl's paper. A backdoor path is any path between response (C) and treatment (A), which goes into A, i.e. any path A <- .... C. For instance, A <- B -> C (a fork) is a backdoor path from C to A. Also, A <- B -> D -> C is a backdoor path. In either case, we should control for B (or either B or D or both), before testing A's effect on C.

In order to de-confound two variables A and C, the backdoor path needs to be broken, i.e. there needs to be independence between two variables somewhere on that path. For instance, A <- B -> D <- E -> C is already a broken path, because the collider D makes B and E independent. In fact, controlling for D here would open a backdoor path and render the analysis confounded.

Try for yourself

So the game of deciding which variables to control for is the game of finding backdoor paths leading from response to treatment (ending in the non-causal direction, into A, A <-), and controlling for some variables in that path which breaks the chain of dependence.

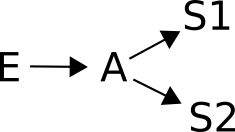

The following examples, from Clarice Weinberg's paper, are a fun way to practice this. The original examples in the paper are a bit macabre, so I've modified the meanings of the variables here, based on a famous spurious correlation4. The causal diagrams are the same, though.

Example 1

Show solution...

Solution to example 1

Many biomedical researchers will be fooled by this example if they don't look at a causal diagram like this one. The reason is that S2 and S1 are obviously correlated, and without the causal analysis, researchers are often confused as to whether a third correlated variable should be controlled for or not. As we learned above, controlling for S1 actually partially controls for A, which partially blocks the effect of E on S2, leading to biased conclusions. The conclusion is one should not control for earlier nobel prizes when assessing the effect of a (constant) exposure on the next one.

Example 2

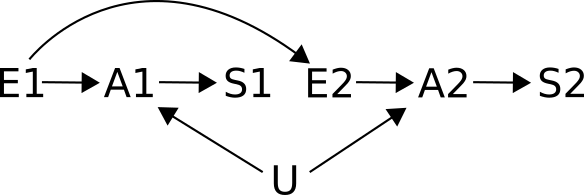

This is an extension of the situation above, adding U as a cause for both S1 and S2. U stands for an unmeasured factor for winning nobel prizes. What about now, should S1 be controlled for when examining the effect of E on S2?

Show solution...

Solution to example 4

Still no. The original point remains, with the addition that now S1 is also a collider A -> S1 <- U, meaning that while A and U are independent, controlling for S1 would make them conditionally dependent, and introduce another confounding bias!

Example 3

The previous examples assumed the exposure to be constant, i.e. the same chocolate consumption for both nobel prizes. What if we introduce multiple exposures?

This extension of the models above has two separate exposures (E1 and E2), each causing separate cognitive abilities (A1 and A2) which lead to nobel prizes (S1 and S2). It is also assumed that the first exposure (E1) affects the later exposure (E2). For instance, if chocolate is addictive. The unmeasured factor U stands as before. Now should S1 be controlled for when trying to estimate the relationship between E2 and S2?

Show solution...

Solution to example 3

There is only one backdoor path from S2 to E2: E2 <- E1 -> A1 <- U -> A2 -> S2. But this path is already blocked by the collider A1. Controlling for S1 is like partially controlling for A1, which opens up this path, and introduces confounder bias! Unless of course we also control for E1 or U, which would break the backdoor path again.

Example 4

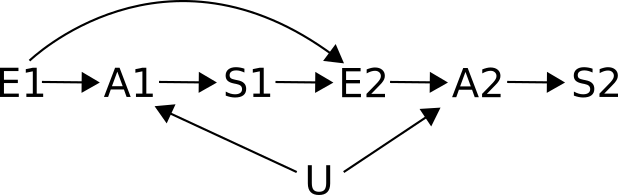

This one is the same as the previous one, with the addition of S1 -> E2, i.e., the first nobel prize might have a causal effect on the second exposure. For instance, after winning a nobel in chemistry, a chocolate eater might decide to eat even more chocolate. Should S1 be controlled for now, when assessing the relationship between E2 and S2?

Show solution...

Solution to example 4

Now there is an open backdoor path, E2 <- S1 <- A1 <- U -> A2 -> S2. This path is open, i.e. has no colliders in it. So unless we control for something, our estimates of the correlation between E2 and S2 will be biased by some confounding! If U is measurable (say, parents' education level), controling for U will close this path. Controling for S1 will close it too!

There is a second backdoor path too: E2 <- E1 -> A1 <- U -> A2 -> S2, but this path is already closed by the collider A1. So even if we could measure A1, and chose to control for it, in order to close the first backdoor path, we would end up opening up this one! So if you control for A1, you'd still need to control for U in order to leave this one closed.

Criticism

In his blog5, Andrew Gelman discussed the merits of this approach, comparing it to the standard imperative to "condition on all pre-treatment variables". Gelman appears to have an issue with colliders, which as explained above, can cause spurious correlations to appear if you control for some variables. He concedes that there might be some situations where different problems with the data cancel each other out, and would be made worse by controlling for only one of them; however he still suggests that the more principled approach is controlling for all pre-treatment variables, and then fix any problems that arise using reasoning.

I think this stems mostly from Gelman's dislike of graphical causal models. And I think this dislike stems from the reasonable criticism that finding the real causal model is difficult. He is no stranger to causal inference, but favors other methods than Pearl's. I don't think they are even very far apart intellectually (everybody prefers their own, or their teachers' methods over others'). Both methods boil down to stating assumptions in a way that will help you realise if you've made some unreasonable ones. This here was an exposition of Pearl's method; perhaps I'll visit the Rubin-Neyman causal modeling framework6 another time.

The end

So there you have it. I hope you found them instructive. Before I was introduced to this method in Judea Pearl's "The book of Why", I, like many of my fellow researchers, resorted to common sense thinking when deciding which variables to control for in my analyses. All too often, I lazily controlled for everything! As the examples above demonstrate, such "common sense" decisions depend on your causal model. Needless to say, any conclusions you draw using a causal model, are dependent on how reasonable your causal assumptions are! Thanks to this method, I now have a principled way to state my causal assumptions, and use them to make better decisions about which variables to control for in my analyses - and so do you!

1. Pearl, Judea. "Causal diagrams for empirical research." Biometrika 82.4 (1995): 669-688.↩

2. Weinberg, Clarice R. "Toward a clearer definition of confounding." American journal of epidemiology 137.1 (1993): 1-8.↩

3. Howards, Penelope P., et al. "“Toward a clearer definition of confounding” revisited with directed acyclic graphs." American journal of epidemiology 176.6 (2012): 506-511.↩

4. Chocolate consumption linked to Nobel Prize winning↩

5. Andrew Gelman: Resolving disputes between J. Pearl and D. Rubin on causal inference↩